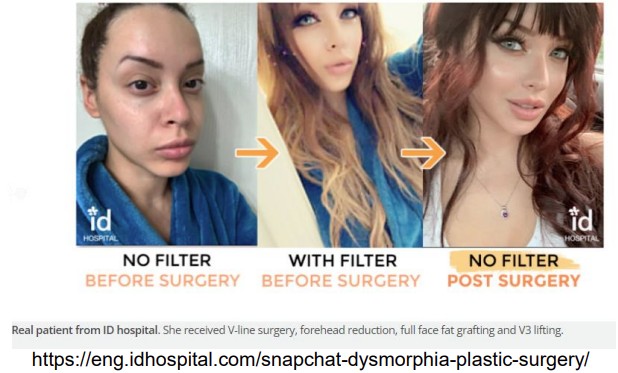

“The phenomenon of people requesting procedures to resemble their digital image has been referred to – sometimes flippantly, sometimes as a harbinger of end times – as “Snapchat dysmorphia”. The term was coined by the cosmetic doctor Tijion Esho, founder of the Esho clinics in London and Newcastle. He had noticed that where patients had once brought in pictures of celebrities with their ideal nose or jaw, they were now pointing to photos of themselves. While some used their selfies – typically edited with Snapchat or the airbrushing app Facetune – as a guide, others would say, “‘I want to actually look like this’, with the large eyes and the pixel-perfect skin,” says Esho. “And that’s an unrealistic, unattainable thing” (Hunt, 2019). Have you actually seen anyone do this? I haven’t in real life, but here’s a picture of someone who is trying to mimic their digital “avatar” in bodyspace – where we live, in what we all used to call, “The real world.” Remember, the digital world is a compelling, interesting place that, for some, is complimenting and beginning to replace the real world:

Now, this says, “no filter” in the post-surgery picture, but her eyes are not dark brown, like the before picture. Contacts? Maybe, but I’d guess the hospital is lying about not having a filter on the picture. I suspect a “small” or “discrete” filter or at least a touch up of the post-surgical photo. Not to lie about the surgery, oh no! Just to “color correct” or maybe “enhance the lighting.” Yeah, right. If even the HOSPITAL can’t put out a picture without manipulating it, what chance does anyone else have? Hunt (2019) continues in the article:

A recent report in the US medical journal JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery suggested that filtered images’ “blurring the line of reality and fantasy” could be triggering body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), a mental health condition where people become fixated on imagined defects in their appearance. Like Esho, Dr Wassim Taktouk uses non-surgical, non-permanent “injectables” such as Botox and dermal fillers to enlarge lips or smooth a bumpy nose. He recalls a client coming to see him in his cream-carpeted Kensington clinic, upset after a date made through an app had gone south. “When she’d met the man, he had been quite disparaging: ‘You don’t look anything like your picture.’” The woman showed Taktouk the heavily filtered image on her profile and said: “I want to look like that.” It was flawless, he says – “without a single marking of a normal human face”. He told her he couldn’t help. “If that’s the picture you’re going to put out of yourself, you’re setting yourself up for disappointment.””

This is commonly called “catfishing,” that is, when your photo looks almost nothing like yourself in person. As the old saying goes, “Honesty is the best policy.” I suppose that nowadays, people do expect a bit of filtering or adjusting of any picture put out on the Internet, but it’s always best to keep the adjustments to a minimum.

“With so much of life now lived online, from dating to job-hunting, recent, quality images of yourself are also a necessity,” (Hunt, 2019) which makes knowing when to say when extremely important. If you post an image of yourself that makes you nearly unrecognizable in person, you risk being branded a liar. Also, Hunt reports that “a 2017 study in the journal Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications found that people only recognised manipulated images 60%-65% of the time.” This lack of recognition coupled with the ever expanding market for more filtering means “it can create ‘unrealistic expectations of what is normal’ and lower the self-esteem of those who don’t use it.”

Another consideration not mentioned in the Hunt article is the fact that we generally use social media in the “lull” time before going to bed or even just waking up in the morning. Our minds are generally more “sleepy” at those times, and with our guards lowered, this may increase the danger of filter dysmorphia. Sleepstation (2024) in the United Kingdom recommends, “We need to be mindful of how often and at what times we connect. Social media usage around bedtime can have major repercussions for your sleep. Ideally, aim to wind-down your usage in the 2 hours before bedtime, but at a minimum, at least 30 minutes before bed. Instead of scrolling through your phone, screen-free time will help prepare you for sleep. Maybe read a book, relax, take a bath, listen to music. Try whatever works to relax you, without involving looking at a screen.”

References

- Hunt, E. (2019). Faking it: how selfie dysmorphia is driving people to seek surgery. The Guardian Web Site: Selfie Dysmorphia Article

- Sleepstation. (2024). Can social media use affect our sleep? Retrieved from Sleepstation Website:Social Media and Sleep Article